Lease/Fractional

US airline fleet is now composed of far more aircraft leased than owned by the airlines operating them

Much of the litigation arising out of aircraft leases results from inadequate diligence in negotiating and documenting the details of the lease agreement

Leaseback: hybrid composite of sale and lease - where as part of the same wrap-around business deal the buyer purchases the aircraft from the seller then turns around and leases it back to the seller for the seller's use

Lease: an agreement, a contract that permits someone else to use an owner's aircraft - aka lease forward

In any lease: (forward or back) the aircraft owner is referred to as lessor and the user as the lessee

Lessor: should check prospective lessee's credit rating before deciding to lease the aircraft to him

If lessee operates or has previously operated aircraft from others, inquire about their experiences with the lessee, especially timely payment and aircraft care and maintenance

Check also the potential for seizure of aircraft by law enforcement agencies if the aircraft is used for illegal purposes - even if aircraft owner is not directly involved in the scheme the aircraft may be seized and forfeited to the government if its owner fails to take reasonable measures to ensure that the aircraft is not being used for such unlawful activities

Aircraft Lease Checklist

- description of aircraft

- name and address of registered owner

- name and address of lessee

- maximum certificated gross takeoff weight of the aircraft

- who is the operator responsible for compliance with FARs governing aircraft operations

- exclusive or non-exclusive use

- inspections and maintenance

- other expenses

- insurance

- crew expenses

- lease payments

- duration, renewal, and termination

Aircraft leasebacks developed primarily as an aircraft sales tool, the leaseback being offered as an incentive to encourage a person to purchase an aircraft she might not feel she could otherwise afford

Sales pitch: under the leaseback, buyer is told she will receive income from FBO's use of the aircraft (rental, charter or flight instruction) - this income will help cover monthly payments for aircraft's financing, inspections, and maintenance - buyer is told she can deduct as business expenses depreciation, insurance, inspection, maintenance, and storage expenses associated with aircraft ownership

BUT

Some dealers are required to purchases a set amount of aircraft annually whether or not they sell them - floor plan financing - so dealers have been known to sell below cost just to relieve the burden of the monthly payments of principle and interest - but in a leaseback the sales price becomes non-negotiable

When the seller presents the leaseback it usually states that seller/lessee does not guarantee any minimum monthly use or payment - usually is either for one year or without a fixed duration - provides that either party may terminate the lease on relatively short notice (10-30 days) without having to show good cause for cancellation - provides that all maintenance will be done by seller/lessee's maintenance shop at seller/lessee's discretion but at owner's cost - maintenance costs can be deducted from rental payments due and if they exceed amount of rental payments due to the owner then the owner must pay the difference

Seller/lessee is continually faced with competitive incentive to keep newest aircraft on the flight line - meaning only keeping aircraft under leaseback for a max of 2 years (regular use by non owner pilots tends to age the aircraft fast!) - incentive to make more deals to make more commissions - if unscrupulous seller/lessee will defer needed maintenance when leased aircraft is in high demand for flight operations (especially when warranty is good) then attempt to catch up during slow periods or falsely bill owners for maintenance not performed (hard for owner to prove)

If owner backs out of leaseback she may find she has recaptured depreciation in the sale and now must file amended income tax returns and pay additional income taxes for the years the aircraft was owned

Beware of wet lease: aircraft owner leases aircraft with flight crew - too much like charter operation

Co-ownership: NOT A PARTNERSHIP - owners are co-owners not partners - recall the risk of vicarious liability with partners - should sign a legal document clearly setting out:

- responsibilities for costs

- means for resolving scheduling conflicts

- and other problems

Fractional Ownership: special kind of co-ownership - economical for users who will need aircraft for between 50 hours and 200 hours annually

For large and turbine-powered multi-engine - 14 CFR 91.501(c)(1) and (3) provide a very narrowly drawn exception permitting operation under Part 91 under a joint ownership or a time-sharing agreement

However only certain itemized expenses of the flight may be charged - meticulous documentation of these charges must be maintained to show compliance with the rule

A true fractional ownership program includes four interlocking primary agreements:

1. the aircraft purchase agreement (between seller and buyers)

2. A joint ownership agreement (among buyers/owners)

3. An aircraft management agreement (between buyers/owners and an aircraft management company)

4. A master interchange agreement (between buyers/owners of all aircraft owned by participants in the management company's fractional ownership program)

Each owner gets access to an appropriate aircraft without the associated management responsibilities for scheduling, crew (not included in light piston fractional ownership), hangar, insurance, inspection and maintenance, at a cost that may be more favorable than either charter rates or full ownership

1/16 (1/32 for helicopters) are the smallest shares - 14 CFR 91.1001(b)(10)

To address safety concerns, the FAA created Fractional Ownership Aviation Rulemaking Committee (FOARC) through an Order in 1999.

The objective of the FOARC was to propose such revisions to the FARs and associated guidance material as may be appropriate with respect to fractional ownership programs.

FOARC was comprised of 27 members representing at least:

- 9 Part 135 operators

- 7 fractional ownership program managers

- 4 airframe manufacturers

- 3 traditional Part 91 corporate flight departments

- 9 traditional aircraft management companies

- 5 industry trade associations

In 2000, the committee presented its recommendations to the FAA

FOARC reached consensus that fractional ownership program operations should continue to be regulated under 14 CFR Part 91

However the committee unanimously recommended FAA adoption of a new subpart K to Part 91 to ensure adequate FAA oversight and surveillance of fractional ownership program managers equal to that experienced by Part 121 or Part 135 operators

Key features include:

1. clarification of responsibility for operational control

2. crew flight and duty time limitations

3. crew training comparable to Part 135 requirements

4. requirement for a drug and alcohol abuse recognition program for all personnel performing safety-related functions

5. aircraft equipment requirements by size, type and class of aircraft (cockpit voice recorder, flight data recorder, ground proximity warning system, thunderstorm detection equipment or airborne weather radar, TCAS)

6. establishment of minimum runway length requirements

7. weather reporting requirements for instrument approaches

8. requirement for an FAA approved maintenance and inspection program

December 22, 2015 - Court decides that flight-sharing websites are illegal - re AirPooler and Flytenow

January 1, 2016 - FAA claims that airplane ride-arranging sites violate federal regulations

June 24, 2016 - Flytenow Flight-sharing Case Seeks Supreme Court Hearing

Air Charter Brokerage

Adobe Acrobat document [203.8 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [264.7 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [44.0 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [2.2 MB]

Adobe Acrobat document [2.1 MB]

Adobe Acrobat document [493.5 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [427.9 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [670.5 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [110.8 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [35.0 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [55.7 KB]

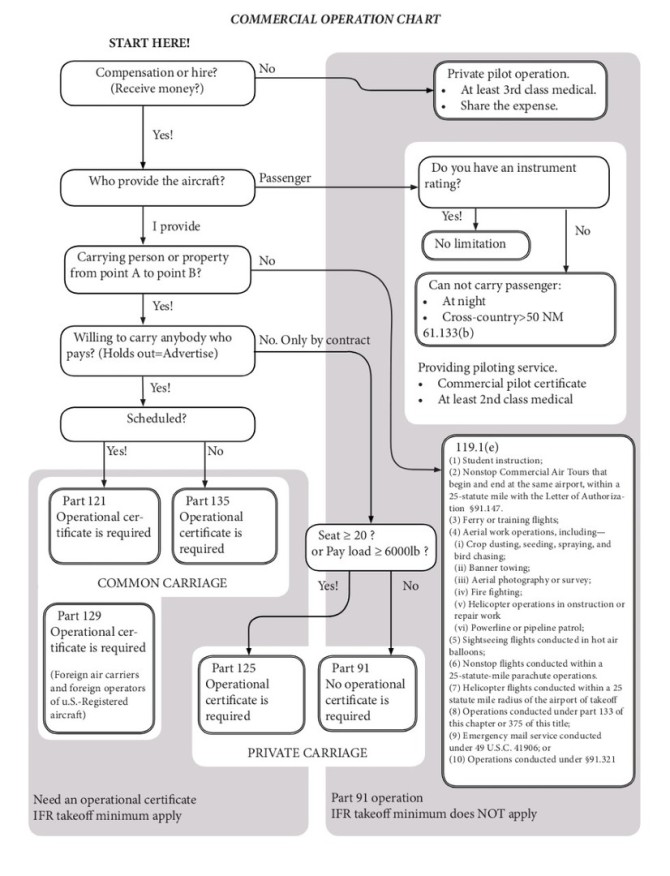

Chart courtesy of Nice Air Aviation

FAA Informational Letter to Pilots5-22-2020 The FAA recognizes that there is a trend in the industry towards using computer and cell phone applications to facilitate air transportation by connecting potential passengers to aircraft owners and pilots willing to provide professional services. Some of these applications enable the provision – directly or indirectly – of both an aircraft and one or more crewmembers to customers seeking air transportation. This letter serves as a reminder to all pilots that, as a general rule, pursuant to 14 CFR (commonly known by industry as the Federal Aviation Regulations FARs) private pilots may neither act as pilot-in-command (PIC) of an aircraft for compensation or hire nor act as a PIC of an aircraft carrying persons or property for compensation or hire. Furthermore, to engage in air transportation a pilot must hold a commercial or airline transport pilot license and must operate the flights in accordance with the requirements that apply to the specific operation conducted (e.g., Part 135). To meet the operational requirements, the pilots must be employed (as a direct employee or agent) by the certificate holder with operational control of the flight (e.g., a Part 135 certificate holder) or must herself or himself hold a certificate issued under 14 C.F.R. Part 119. Another common pitfall to be aware of is the “sham dry lease” or the “wet lease in disguise.” This situation occurs when one or more parties act in concert to provide an aircraft and at least one crewmember to a potential passenger. One could see this, for example, when the passenger enters into two independent contracts with the party that provides the aircraft and the pilot. One could also see this when two or more parties agree to provide a bundle (e.g., when the lessor of the aircraft conditions the lease – whether directly or indirectly – to entering into a professional services agreement with a specific pilot or group of pilots. This type of scenario is further discussed in Advisory Circular (AC) 91-37B, Truth in Leasing.

An additional caution to consider is flight-sharing. Section 61.113(c) of Title 14 of the CFR allows for private pilots to share certain expenses. Pilots may share operating expenses with passengers on a pro rata basis when those expenses involve only fuel, oil, airport expenditures, or rental fees. To properly conduct an expense sharing flight under 61.113(c), the pilot and passengers must have a common purpose and the pilot cannot hold out as offering services to the public. The “common-purpose test” anticipates that the pilot and expense-sharing passengers share a “bona fide common purpose” for their travel and the pilot has chosen the destination. Communications with passengers for a common-purpose flight are restricted to a defined and limited audience to avoid the “holding out” element of common carriage. For example, advertising in any form (word of mouth, website, reputation, etc.) raises the question of “holding-out.” Note that, while a pilot exercising private pilot privileges may share expenses with passengers within the constraints of § 61.113(c), the pilot cannot conduct any commercial operation under Part 119 or the less stringent operating rules of Part 91 (e.g., aerial work operations, crop dusting, banner towing, ferry or training flights, or other commercial operations excluded from the certification requirements of Part 119). For more information on sharing flight expenses, common purpose, and holding out see:

Unauthorized 135 operations continue to be a problem nationwide, putting the flying public in danger, diluting safety in the national airspace system, and undercutting the business of legitimate operators. If you have questions regarding dry-lease agreements or sharing expenses, please review the FARs and ACs. Additionally, you may contact your local Flight Standards District Office for assistance or seek the advice of a qualified aviation attorney. |

|

Important Charter Guidance for Pilots and

Passengers Today, booking a charter flight can be as easy as tapping a few buttons on your mobile device. But that doesn’t mean the flight is legal or safe. The FAA’s top priority is ensuring the safety of the traveling public, and it’s critical that both pilots and passengers confirm that the charter flights they’re providing and receiving comply with all applicable Federal Aviation Regulations. If you pay for a charter flight, you are entitled to a higher level of safety than is required from a free flight from a friend. Among other things, pilots who transport paying passengers must have the required qualifications and training, are subject to random drug and alcohol testing, and the aircraft used must be maintained to the high standards that the FAA’s charter regulations require. The FAA recently sent a letter about this issue to a company called Blackbird Air that created a web-based application that connects passengers with pilots. The letter emphasizes an FAA policy about the requirements for pilots who are paid to fly passengers. The policy states that pilots who are paid to fly passengers generally can’t just hold the required Commercial or Airline Transport pilot license – they also must be employed by the company operating the flight, which must hold a certificate issued under Part 119 of the Federal Aviation Regulations. Or the pilots must themselves hold a Part 119 certificate. Any pilot who provides charter flights without complying with the Part 119 certificate requirement would be violating the Federal Aviation Regulations – even if they possess a Commercial or Airline Transport Pilot license. The FAA’s determination has been upheld in federal court. A current listing of FAA-licensed charter providers is available here.

Q&A Q: I have a Commercial/Airline Transport Pilot license. Why can’t I simply sign up on a web-based app as a pilot for hire and get paid to fly passengers? A: The FAA has determined that pilots who participate in a for-hire service are holding themselves out as providers of common carriage. As such, they must be employed by the company operating the flight that holds a certificate issued under Part 119 of the Federal Aviation Regulations or must themselves hold a certificate issued under Part 119. The FAA expects to issue additional written guidance on this issue soon. Pilots who have questions about the legality of a planned operation should contact their local FAA Flight Standards District Office. Q: I’m a pilot who has conducted flights through Blackbird but I don’t work for a Part 119 certificate holder nor do I have a Part 119 certificate. What’s going to happen to me? A: At this time, the FAA is reminding pilots and alerting passengers about the requirement that Commercial pilots and Airline Transport Pilots must also conduct charter flights under proper Part 119 certification. The FAA does not plan to take enforcement action against pilots who have conducted prior flights using the Blackbird app without a Part 119 certificate. However, any pilot who doesn’t meet these requirements and conducts for-hire flights going forward could face enforcement action from the FAA. Q: I was a passenger who paid for a charter flight through Blackbird and the flight was not operated under a Part 119 certificate. Do I face any sanctions? A: At this time, the FAA does not plan to assess sanctions against any passenger who paid for any such flight. We note, however, that if a passenger accepts operational control over a flight, which means accepting responsibility for the safety of the flight and that it complies with all applicable regulations, that passenger may be responsible for any regulatory violation related to the flight. This could include violations related to the failure to comply with part 119 certification requirements. The FAA strongly encourages passengers to ensure their charter flights meet all applicable regulations. Q: Is the FAA saying that all flights conducted through Blackbird could potentially violate the Federal Aviation Regulations? A: No. Flights piloted by properly certificated pilots who are conducting the flight for companies that hold Part 119 certificates, or flights flown by pilots who themselves hold a Part 119 certificate, may comply with the Federal Aviation Regulations. Q: As a passenger, what should I look for when making arrangements for a charter flight? How can I know if my flight is legal? A: A current list of FAA-certificated charter providers is available here. Pilot certificate information is available here. Passengers also should ask the pilot if their specific flight is conducted under a Part 119 certificate. Q: When did the FAA determine that pilots who sign up with on-line for-hire services are holding themselves out as engaged in common carriage requiring a Part 119 certificate? A: This has been the FAA’s longstanding policy consistent with the regulations that govern common carriage operations. The FAA issued determinations in 2014 to companies called Flytenow and Air Pooler that apply this longstanding policy to web-based initiatives. Blackbird’s platform is similar to those companies’ platforms. Q: When was the court ruling that upheld the FAA’s determination? A: In 2015, the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld the FAA’s determination in the case Flytenow, Inc. v Federal Aviation Administration.

|

Misuse of Expense Sharing and Understanding Pilot Privileges Notice Number: NOTC2238 - February 2022

Unauthorized 135 operations continue to be a problem nationwide, putting the flying public in danger, diluting safety in the national airspace system, and undercutting the business of legitimate operators. This letter is a follow-on to the May 2020 Informational Pilot Letter and a continuing effort to remind all pilots to be on the lookout for possible illegal operations. This letter will focus on two ongoing issues; first, the misuse and/or misunderstanding of expense sharing between pilots and passengers. Second, the apparent lack of understanding of pilot privileges and limitations versus operating rules.

Expense Sharing Reminders: (See AC- 61-142)

When compensation is exchanged for transportation, the public expects, and the regulations demand, a higher level of safety. As a general rule, private pilots may neither act as PIC of an aircraft for compensation or hire nor act as PIC of an aircraft carrying persons or property for compensation or hire. Refer to 14 C.F.R. § 61.113(a). Section 61.113(b) through (h) contains seven exceptions to this general prohibition against private pilots acting as PIC for compensation or hire. One commonly misapplied provision is the expense sharing exception contained in § 61.113(c), which permits a pilot to share the operating expenses of a flight with passengers provided the pilot pays at least (may not pay less) his/her pro rata share of the operating expenses of that flight. Those expenses are strictly limited to fuel, oil, airport expenditures, or rental fees. In addition, only reimbursement from the passengers is allowed.

(NOTE: The § 61.113 exceptions also apply to ATP and commercial certificate holders who are exercising private pilot privileges and also broadly applies under § 61.101 and § 61.315.)

Pilots must also remember, if they want to share expenses under § 61.113(c), they must not “hold out” to the public or a segment of the public to expense share because that would put them into the realm of common carriage—i.e., (1) the holding out of a willingness to (2) transport persons or property (3) from place to place (4) for compensation or hire. As discussed more below, common carriage changes the operating rules under which the flight must be conducted and, necessarily, triggers the higher certification and qualification requirements for pilots required by those operating rules. (See AC 120-12A).

A major point of emphasis to keep in mind regarding expense sharing flights is the “common purpose test”. This means, that the pilot must have his or her own reason for traveling to the destination, not simply for the transportation of the passengers.

- For example: A private pilot is flying to Stillwater, Oklahoma, to visit her mother in the hospital over the weekend. Five of her friends would be coming with her to attend a football game that same weekend. She CAN legally share expenses because she has a reason to fly to Stillwater (visit her mother) not simply to transport her friends. Expanding the same scenario; if she has too many friends going to the football game that she has to make a second trip to pick up the rest, she CANNOT legally share expenses on the second trip because her purpose for flying to Stillwater was complete when she arrived the first time. The second flight was solely for the transportation of passengers.

Distinction Between Pilot Privileges and Operational Rules:

It has come to the attention of the FAA that, in general, pilots do not know or completely understand that the privileges and limitations of their certificates are separate and distinct from the operational rules required to conduct a flight, or to put it simply, pilot certification rules vs. operational rules. A person who holds an ATP Certificate or a commercial pilot certificate may act as PIC of an aircraft operated for compensation or hire and may carry persons or property for compensation or hire. However, simply holding a commercial pilot or ATP certificate does not end the inquiry. A commercial pilot or ATP must meet the qualification requirements not only of part 61 but also the part under which the operation is conducted and the operator must hold the proper operating authority. Most operations involving the carriage of persons for compensation require the operator to hold a certificate under part 119 authorizing such operations to be conducted under part 135 or 121. (See 14 C.F.R. §§ 119.1 et seq., 135.1, and 121.1, and definitions codified at § 110.2) A pilot, for a flight operated under part 135 or 121,must meet additional qualification requirements like training, checking, and experience requirements. Therefore, in addition to ensuring compliance with the applicable pilot privileges and limitations in part 61, prior to conducting any operation a pilot must also determine what operational rules the flight is conducted under, whether the operator has the appropriate operational certification (a part 119 certificate), and whether the pilot has the requisite qualifications. Unless a valid exception from operational certification rules applies pursuant to § 119.1(e), operators (could be the pilot under certain circumstances) cannot engage in common carriage, e.g., holding out, unless they are operating in accordance with an air carrier certificate or commercial operating certificate. (See AC 120-12A).

- An example of pilot confusion over these distinctions is as follows: During a conversation between an experienced part 135 pilot and an Aviation Safety Inspector (ASI), the pilot said “Doesn’t part 61 (61.133) say that a commercial pilot can transport persons or property for hire?” The ASI answered “Yes...but what does the rest of the sentence say?” …provided the person is qualified in accordance with the applicable parts of this chapter that apply to the operation…” The ASI then asked “Do you fly under part 61 or under an operating rule such as part 91 or part 135?” The pilot suddenly replied “Ohhhh! I see” he said, “part 61 is privileges and limitations, but we also have to comply with the operating rules. Got it!”

Commercial and ATP pilots should also remember that although these certificates allow them to receive compensation and operate aircraft carrying people for compensation or hire, they themselves cannot hold out the public unless they have been issued a part 119 certificate. (See Legal Interpretation from Mark Bury to Rebecca B. MacPherson (August 13, 2014)).

If you have questions regarding sharing of operating expenses, holding out, or pilot certification rules versus operating rules, please review the FARs, Advisory Circulars, and Legal Interpretations referenced herein and below. Additionally, you may contact your local Flight Standards District Office for assistance or seek the advice of a qualified aviation attorney.

goldberg.pdf

Adobe Acrobat document [190.2 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [715.6 KB]

Microsoft Power Point presentation [5.6 MB]

Adobe Acrobat document [966.2 KB]

Microsoft Power Point presentation [5.0 MB]

Adobe Acrobat document [151.4 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [96.7 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [110.1 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [156.2 KB]

Contact Me

Sarah Nilsson, J.D., Ph.D., MAS

602 561 8665

You can also fill out my

Get Social with Me

Legal Disclaimer

The information on this website is for EDUCATIONAL purposes only and DOES NOT constitute legal advice.

While the author of this website is an attorney, she is not YOUR attorney, nor are you her client, until you enter into a written agreement with Nilsson Law, PLLC to provide legal services.

In no event shall Sarah Nilsson be liable for any special, indirect, or consequential damages relating to this material, for any use of this website, or for any other hyperlinked website.

Steward of

I endorse the following products

KENNON (sun shields)