- What are student-faculty partnerships?

Guiding principles and definition of partnership

3 principles: respect, reciprocity, responsibility

Norms in higher education that need to be revised

- Preliminary questions about student-faculty partnerships

Responses to preliminary questions you may have about student-faculty partnerships

- Partnerships with students

Examples of student-faculty partnerships

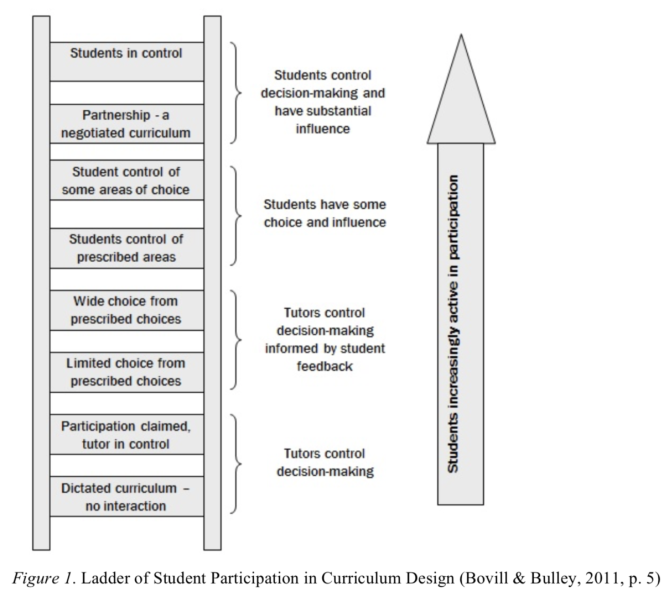

Starting with faculty-driven and faculty-developed approaches and many varieties of student-faculty partnership involving different types of students, a focus on different elements of learning and teaching, and different levels of partnership

- Program-level approaches to student-faculty partnerships

Examples of individual, program-level, and institutional-level student-faculty partnerships

Outlines of programs that support:

(1) designing or redesigning a course before or after it is taught;

(2) analyzing classroom practice within the context of a course while it is being taught; and

(3) developing research partnerships that catalyze institutional change

- Outcomes of student-faculty partnerships

Research into the outcomes of partnerships

Mutual benefits for students and faculty, including:

(1) enhancing engagement, motivation, and learning;

(2) developing metacognitive awareness (awareness of one’s own thinking and action) and a stronger sense of identity; and

(3) improving teaching and the overall classroom experience

- The challenges of student-faculty partnerships

Cautions to prepare you for challenges you may face in adopting a partnership approach

Necessity of working to find a balance of participation, power, and perspective;

The imperative to consider perspectives from underrepresented students and faculty;

The necessity of being careful and intentional regarding the language we use to describe the work;

The wisdom of starting small rather than taking on too much too quickly;

The danger of adopting processes and programs uncritically and embracing a one-size-fits-all model; and

The risk of assuming that all students and faculty will be receptive to the idea of partnership

- Practical strategies for developing student-faculty partnerships

Practical strategies for developing partnerships

(1) getting started with student-faculty partnerships

(2) sustaining and deepening student-faculty partnerships; and

(3) negotiating roles and power within partnerships

- Further questions about student-faculty partnerships

Discussion of further questions you may have

How to pursue partnerships in an institution that might not have a culture conducive to doing so

How to think about the role of change in student-faculty partnerships

How to return to “regular” teaching and learning after having been in partnership

- Assessing practices and outcomes of student-faculty partnerships

Outline of approaches to assessing the processes and outcomes of student-faculty partnerships

- Next steps … toward a partnership movement?

Some reflections on next steps in and toward a partnership movement

Short summary of the main insights and arguments offered throughout the book

PARTNERSHIP – based upon RESPECT – RECIPROCITY – SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

3 foundational beliefs:

- Students have insights into teaching and learning that can make our and their practice more engaging, effective, and rigorous

- Faculty can draw on student insights not only through collecting student responses but also through collaborating with students to study and design teaching and learning together

- Partnerships between students and faculty change the understandings and capacities of both sets of partners – making us all better teachers and learners

SaLT: Students as Learners and Teachers

ASSESSEMENT: stepping back from and analyzing progress in any educational endeavor – learning, teaching, research, pedagogical partnership – either in a formative way (during the process with the goal of using what is gathered to revise approaches) or in a summative way (with the goal of measuring and making adjustments about what has been learned, taught, or accomplished after the process is completed). In some contexts, assessment and evaluationare used interchangeably; in others, the way we define assessmenthere is more frequently called evaluation.

SERVICE LEARNING: an approach to teaching and learning that integrates meaningful community service with teaching and that supports regular, ongoing reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities

CHAPTER 1

Respect – reciprocity – shared responsibility

All three require and inspire trust, attention, and responsiveness – listening not only with “open eyes and ears but also open hearts and minds” – lead to informed action and interaction

Respect is an attitude.

It entails taking seriously and valuing what someone else or multiple others bring to an encounter. It demands openness and receptivity, it calls for willingness to consider experiences or perspectives that are different from our own, and it often requires a withholding of judgment.

Teacher-student relationships have to be respectful, and the respect must be in both directions.

While respect is an attitude, reciprocityis a way of interacting. It is a process of balanced give-and-take; there is equity in what is exchanged and how it is exchanged. Therefore, what this principle embodies is the mutual exchange that is key to student-faculty partnerships.

The most basic manifestation of reciprocity in partnerships occurs when students offer their experiences of, and perspectives on, what it is like to be a learner in a course where faculty offer their experiences of, and perspectives on, teaching that course. Reciprocity also involves students taking on some responsibility for teaching and faculty re-envisaging themselves not only as teachers, but also as learners alongside their students.

Participating in this project gave me a sense of students being able and wanting to take certain pedagogical responsibility, and the counter of that is me taking a learning responsibility. When both students and faculty take more responsibility for the educational project, teaching and learning become community property with students recognized as active members of that community and collaborative partners equally invested in the common effort to engage in, and support, learning.

- Trust and respect

- Shared power

- Shared risks

- Shared learning

Partnerships rarely emerge suddenly in full bloom; instead, they grow and ripen over time as we engage with students.

We define student-faculty partnership as a collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualization, decision making, implementation, investigation, or analysis.

Partnership involves negotiation through which we listen to students but also articulate our own expertise, perspectives, and commitments. It includes making collaborative and transparent decisions about changing our practices in some instances and not in others and developing mutual respect for the individual and shared rationales behind these choices. Indeed, it means changing our practices when appropriate, but also reaffirming, with the benefit of students’ differently informed perspectives, what is already working well.

Initiating partnerships requires stepping out of traditional roles, something that always is a challenge both to imagine and to do.

We envision partnership as creating the conditions for curiosity and common inquiry, breaking down the barriers that often distance students from faculty.

Students will work hard and engage deeply when they experience learning as personally meaningful.

We can strive to act as partners, equally invested in the common goal of learning. Embracing change like this requires openness to what Shulman has called “visions of the possible” that can inspire our thinking and practice, even when such visions might be offering just a glimpse of a distant horizon.

CHAPTER 2

Indeed, most students are neither disciplinary nor pedagogical experts. Rather, their experience and expertise typically is in being a student – something that many faculty have not been for many years. They understand where they and their peers are coming from and, often, where they think they are going. As experienced students, they are experts about sitting in classes, understanding new concepts, and creating their own learning.

We advocate cultivating or deepening respect for students as partners based on their positions, experiences, and insights as learners. We propose that you think of students as legitimate informants on the student experience – those with perspectives we cannot have as teachers.

People typically find time for the things they consider most important. Time investments up front can pay off later as students take a more active role in the learning process. Most students recognize that having a hand in designing their own learning is far more engaging, interesting, and meaningful as a form of education. If students are invited to work in partnership, even just for a bounded and focused part of the course, their engagement deepens, and they begin to shift their thinking. Moving toward partnership with students, by taking slow, cautious steps to ensure that students trust the changes, is one of the best ways to inspire students’ openness to designing their own learning.

Students can get credit by:

- Directed studies?

- Conferring a formal title on their work

- They can include on their resumes

- Anything to show that we value their participation

Consider starting small, perhaps by working with a handful of students or talking with a few like-minded colleagues, beginning with people you suspect will be open to the idea of partnership. Set attainable goals such as redesigning a single assignment with students in a course rather than trying to enlist an entire department to redesign the curriculum in partnership with students.

Be alert for sources to support and fund your partnership work. Often institutions have internal innovation grants, and some external funders are in search of unique and distinctive learning and teaching projects.

Even if the ends of a course are fixed, the means are not!

Typically, some flexibility exists within courses and programs for faculty and students to design learning and teaching in ways that they consider most effective for developing professional knowledge, skills, values, and competencies.

There is no single best career stage for partnership, and we think this work is appropriate for faculty of all ages and stages. However, because faculty roles and responsibilities vary widely across disciplines and types of institutions, we encourage you to think carefully about how partnership connects to institutional values, how it fits into your career development, and how it might be both supported and rewarded on your campus.

The goal of student-faculty partnership work is not change for change’s sake but rather to achieve a deeper understanding of teaching and learning that comes from shared analysis and revision.

Faculty and student partners produce minor revisions, and in others they completely overhaul a course, assignment, or approach. What kind of change is made and how rapidly should be carefully considered. Indeed, too many changes made too quickly can be disruptive and might even be detrimental, so partners need to think carefully about what kind and extent of change is advisable for all involved.

Regardless of the scope and pace of change that takes place, there is reciprocity in the process both faculty and students learn from their interactions, are more informed and thoughtful as a result, and carry their deepened awareness and more developed capacities into other contexts and relationships.

The biggest impact that change has is upon attitudes: understanding teaching and learning as shared responsibilities rather than responsibilities distinguished and divided between students and faculty.

Faculty should be wary of claiming partnership without allowing real opportunities for students to collaborate. If, however, you present the opportunity as one in which you are truly willing to share – not give up, but share – power and responsibility in conceptualizing, implementing, or assessing some part of the class, and if you stay in open and honest dialogue with students about the processes as well as the outcomes, then they are not likely to think you are experimenting on them. Students may see the experience as experimenting with them, and that often is exciting for all involved.

Establish rapport.

Discuss the focus for your work together.

Begin to clarify the roles students and faculty will play in the collaboration.

Many students (and faculty) may not have undertaken anything similar before, so give everyone time to imagine what the partnership will involve and to ask plenty of questions. Try to build in flexibility so you can adjust roles and responsibilities to suit individual and group skills and interests in the early stages of the partnership.

CHAPTER 3

- Designing a course or elements of a course, including assignments

Course design is perhaps the most important step in effective teaching. The design process is ripe for partnership because it allows for planning and deliberation, affording faculty and students an opportunity to develop comfort with, and confidence in, the shared work. Many faculty begin by codesigning elements of a course with students; others co-create entire courses.

How students and faculty have worked in partnership to explore these different areas:

- Creating approaches to helping less advanced students understand difficult concepts

- Redesigning a virtual learning environment

- Deciding which cases and content will be studied

- Developing a class consensus on what students need to do to achieve the learning goals and to earn course grades

- Encouraging students to write their own essay questions

- Inviting students to choose assignment types, content, timing, and weighting of assignments

- Challenging students to author multiple-choice questions

- Working with students to identify course objectives

PAL: Peer-assisted learning

PeerWise– enables students to author multiple-choice questions – free online software created by Paul Denny at the University of Auckland

Professor asks students what they want to get out of class – the idea that you trust us is awesome – we are adults – personally relevant to their lives and to their future careers.

- Responding to the student experience during a course

Examples:

- Have students select photos as prompts for discussions in class

- Invite former students to interview current students to access their experiences in a challenging course

- Support students in the development and trying out of problem-based laboratory experiences

- Draw on students’ social bookmarking to shape course content

- Collaborate to create course content

- Regularly gather and respond to feedback from students

- Assessing student work

Collaborating with students to assess their learning often seems like the riskiest approach to partnership for many faculty.

If we set up partnerships focused on assessment, we can acknowledge established standards in our fields while helping students to better understand and act within our disciplinary contexts. We can also contribute to enhancing their understanding of assessing learning outcomes in ways that are crucial to developing their knowledge of learning how to learn.

Designing assessment FOR learning in contrast with typical forms of assessment OF learning.

Some faculty are moving away from forms of assessment that are just testing what a student has learned, and instead are embracing methods of assessment that test what a student has learned in addition to being assessment through which students learn.

When criteria for grading and other forms of summative assessment are negotiated, student learning and engagement deepen. Understanding grading and feedback criteria helps students meet expectations more effectively and comprehend more fully where (and why) they did not adequately demonstrate their learning.

Taking students’ self-assessments of the challenges of a particular content area and putting them into a guide makes assessment into a proactive process for future students, as well as a reflective one for current students. Similarly, having students engage in their own summative assessment makes them actively reflect on their understanding, not just focus on the right answer. These shifts make students far more active in, and responsible for, their learning.

Adobe Acrobat document [931.3 KB]

University of Washington DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, Technology)

Association of Higher Education and Disability: an umbrella advocacy group that can put faculty members and staff in touch with local and national experts and resources.

Center for Applied Special Technology: One-stop web resource for learning about universal design for learning. Updated in mid-2014 with new content specifically for higher education applications of UDL.

CollegeSTAR [Supporting Transition, Access, and Retention]: a grant-funded project that enables participants to partner in the development of initiatives focused on helping postsecondary campuses become more welcoming of students with learning and attention differences.

The Center for Teaching and Faculty Development: has several guides to designing accessible multimedia that can be used in an online environment.

National Center on Universal Design for Learning: General Resources for implementation in higher education, especially the UDL Guidelines Worksheet

Adobe Acrobat document [246.7 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [241.0 KB]

CHAPTER 4

Developing projects that reach beyond a single classroom or an isolated faculty member

- Designing or redesigning a course before or after it is taught

Afford faculty and student partners the opportunity to collaborate in the process of co-creating engaging courses.

When students are given choice about the assignment methods to be used, they frequently choose to challenge themselves.

Written job descriptions: for their roles and expectations of one another – the more detailed the job descriptions the more successful they will be when they work together

Partnership in learning is beneficial to all

CDT: course design team

Backward-design approach: first developing course goals and then building pedagogical strategies and learning assessments on the foundation of those goals

- Analyzing classroom practice within the context of a course while it is being taught

Our attention is on an already planned curriculum, or partially planned one, and navigating while course is unfolding.

SCOT: students consulting on teaching program

Roles in SCOT include:

- Recorder/observer – the student records, in writing, what went on in the classroom and gives the record to the instructor

- Faux student – the student takes notes as though he or she were a student in the class and returns the notes to the instructor

- Filmmaker – the student films the class and creates a DVD for the instructor

- Interviewer – the instructor leaves the classroom for 15 minutes while the student conducts an interview with the class

- Primed student – the student meets with the professor prior to class to receive instructions on what to watch for (e.g. how often students are getting involved in the discussion; which activities are most engaging, etc.)

- Student consultant – the instructor asks the student consultant for feedback and suggestions about classroom activities or particular areas of interest

- Developing research partnerships that catalyze institutional change

SoTL: Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

IRB: Institutional Review Board

AI: Appreciative-inquiry – a strengths-based approach and this optimistic slant, along with this being a student-faculty partnership project, contributed to faculty reporting being very positive about the project and considering the findings to be particularly powerful. The initial training phase of the AI process was fundamental in setting the tone for the relationship between students and staff… the relaxed and interactive nature of the training session allowed many student/staff barriers to be removed. Out input and ideas were valued and respected, enabling us to confidently share our thoughts and ideas. Subsequent face-to-face meetings were held, which improved team cohesion between us and the academic staff and saw the shaping and development of the project.

Students as Change Agents: What is different about the change agents concept is that it takes the idea of students as researchers into a different dimension from the discipline-based research usually discussed in higher education, with a new focus on researching pedagogy and curriculum delivery. Students apply and develop their research expertise in the context of their subject, taking responsibility for engaging with research-led, evidence-informed change, and promoting reflection and review at a departmental and institutional level.

Working with their theoretical model of students as change agents, Dunne & Zandstra (2011) differentiated among:

- Students as evaluators, involving processes through which the institution and external bodies listen to the student voice in order to drive change;

- Students as participants, such as efforts that emphasize institutional commitment to greater student involvement in changes to teaching, learning, and institutional development;

- Students as partners, engaging students as co-creators and experts; and

- Students as agents for change, which requires a move from institution-driven to student-driven agendas and activity.

The above categories are not mutually exclusive.

Benefits of moving from individual to programmatic approaches:

- Moving further from pedagogical solitude toward teaching as a community property

- Securing institutional and financial support

- Shifting institutional culture

Drawbacks of moving from individual to programmatic approaches:

- Potential loss of freedom and spontaneity

- Potential for ossification – may stifle development if new efforts

- Potential for imposition – even well-intended enthusiasm can lead to imposition

Recommendations for those in faculty development roles – those in a position to support and guide others in developing student-faculty partnerships – directors or coordinators of teaching and learning centers, faculty members in liaison roles, or faculty developers can all facilitate and support student-faculty partnerships by:

- Serving as intermediaries: facilitate the development of new relationships between students and faculty who may not be accustomed to approaching one another and building these kinds of partnerships – when the institution sends a clear message that such partnerships are valued and desirable, faculty will be more likely to be inclined to embrace such partnerships and seek support for them.

- Building on existing commitments among faculty: many faculty have been working in partnership with their students for years.

- Promoting and practicing co-creative approaches in professional development forums: a large proportion of new faculty undertake preparatory teaching programs and courses such as Postgraduate Certificates in Learning and Teaching. These programs emphasize the importance of reflection on, and critical analysis of, one’s own teaching practice.

- Acting as a bridge between different parts of the university and influencing policy: faculty developers sit in a middle layer between faculty and administrators – their role involves support, liaison, advice, investigation, quality assurance, as well as teaching and learning. May also be in a position to influence the institution’s public commitment to student-faculty partnerships.

CHAPTER 5

Partnership as a means to reach our goals in higher education: decades of research indicate that close interaction between faculty and students is one of the most important factors in student learning, development, engagement, and satisfaction in college.

Frequent and meaningful faculty-student interaction is a central characteristic of all high-impact educational practices.

Partnership is a highly flexible practice.

Authentic partnership is not automatically or easily accomplished.

All interactions should be viewed through a partnership lens:

- Classroom

- Faculty mentoring undergraduate research

- Facilitating service-learning

- Designing and leading study-abroad experiences

- Advising living-learning communities

A note about research methodology: qualitative research methodologies and methods to access and analyze student and faculty experiences and outcomes – evaluation research methodology, case study methodology, action research, or participatory action research.

- Ask participants to complete questionnaires and surveys

- Conduct interviews and focus groups

- Analyze feedback faculty and students offer during their participation

- Use constant comparison approach or elements of grounded theory

- Start by engaging in open coding: process of breaking down, examining, comparing, conceptualizing, and categorizing data

- Then identifying key and emerging themes within data

Outcomes of partnership: similar for both students and faculty

- Engagement – enhancing motivation and learning – engagement means serious interest in, active taking up of, and commitment to learning – autonomy and agency are also important factors that contribute to students’ taking more responsibility for their own learning – independent engagement makes students more likely to adopt deep approaches to learning.

Student-faculty partnerships consistently deepen student engagement, motivation, and learning – AKA pedagogy of mutual engagement

Student outcomes:

- Enhanced confidence, motivation, and enthusiasm – result of students having a range of opportunities – to be taken seriously as collaborators in explorations of teaching and learning – develop the language to name what they know about those processes and deepen that knowledge in dialogue with faculty – then apply that understanding with their faculty partners – influencing teaching practice as well as enhancing their own educational experiences – this leads to productive action

- Enhanced engagement in the process, not just outcomes, of learning – shift in focus from outcomes often in form of grades to processes that focus on learning itself – “look at the big picture” – come to understand the aim for each exercise from an instructor’s perspective

- Enhanced responsibility for, and ownership of, their own learning – rather than primarily satisfying expectation and standards others have created for you

- Deepened understanding of, and contributions to, the academic community – learning goes in multiple directions and benefits all involved

Faculty outcomes:

- Transformed thinking about and practices of teaching – much more engaging and effective to work WITH students rather than AGAINST them – partnerships can illuminate how to move from inherited routines to more thoughtful and more effective practices

- Changed understandings of learning and teaching through experiencing different viewpoints – faculty and students alike expand their perspectives on one another’s and their own work – through partnership faculty gain new angles of vision – insights that students offer and that we as faculty cannot gain without student input

- Reconceptualization of learning and teaching as collaborative processes – this does not mean that faculty relinquish their responsibilities as experts in their fields and as an authoritative presence in the classroom, but it does mean that they have adapted their approach to teaching and their understanding of learning – see students more as colleagues, more as people engaged in similar struggles to learn and grow – shift in attitude and approach, from student-as-consumer view of learning and sage-on-the-stage model of teaching to a conceptualization of both students and faculty members as learners as well as teachers

- Awareness – developing metacognitive awareness and a stronger sense of identity: both students and faculty make significant gains in developing deeper metacognitive awareness connected with a stronger sense of identity – having to articulate our thinking makes that thinking clearer and open to analysis, revision, and changed behavior – when we become aware of our thinking, we can act in more intentional and informed ways

Self-authorship: process of actively creating a self – an identity and way of being – students are engaged in this process all the time, and at a fast pace – they are expected to change, grow, and master all kinds of new information virtually daily – for faculty the expectation is different – we are no longer formally students, but we see ongoing learning as an integral part of our identities as teachers and scholars, even if we do not expect to change as rapidly or as thoroughly as our students do.

The process of creating a self – an identity and way of being – is the process of internally coordinating one’s beliefs, values, and interpersonal loyalties rather than depending on external values, beliefs, and loyalties.

Such self-authorship is informed by 3 dimensions of development that intertwine:

- How we know or decide what to believe (epistemological dimension)

- How we view ourselves (intrapersonal dimension)

- How we construct relationships with others (interpersonal dimension)

Awareness outcomes for students:

- Developing metacognitive awareness

“Awareness of their awareness” – you really don’t understand the way you learn and how others learn until you can step back from it and are not in the class with the main aim to learn the material of the class but more to understand what is going on in the class and what is going through people’s minds as they relate with that material

As a student I am more conscious of my own goals for taking a particular class and the big cohesive ideas that emanate from the individual lessons in the class. I constantly evaluate the level to which I engage with the material I learn. I may not necessarily change my strategy for engaging with ideas, but I realize that I have become much more conscious of my level of engagement. I realize that I have become more aware of my own learning patterns.

- Developing a stronger sense of identity

Awareness outcomes for faculty:

- Developing metacognitive awareness

Faculty see themselves reflected back, but the image is inflected by the students’ perspectives.

The combination of what is familiar and what might be new or surprising prompts faculty to develop what one faculty member called his own “3rdperson perspective” – a more distanced and more informed perception of his practice.

- Developing a stronger sense of identity

Partnership in their teaching made faculty better scholars as well, helping them to integrate the various dimensions of their professional identity.

- Enhancement – improving teaching and the classroom experience

Enhancement outcomes for students:

- Becoming more active as learners

- Gaining insight into faculty members’ pedagogical intentions – what have you done to improve your own learning

- Taking more responsibility for learning – for your own education

Enhancement outcomes for faculty:

- Becoming more reflective and responsive

“Mirror in motion” – an understanding of reflection that admits of ongoing movement, change, and interaction, so that “success” in reflective practice is a matter of agility, mobility, flexibility, and, importantly, of the interdependence of one’s movements with those of others on and beyond the reflected scene.

Integrating students into the “cycle of interpretation and action” that constitutes reflective practice provides participants with a unique forum within which to access and revise their assumptions, engage in reflective discourse, and take action in their work.

- Creating more democratic classrooms in which partnership is the norm

Pedagogy of mutual engagement – teachers and learners together engaged in intellectual collaboration

Outcomes of partnership for programs and institutions

Radical collegiality – supports students as agents in the process of transformative learning – model through which teachers learn WITH and FROM students through processes of co-constructed, collaborative work – such an approach recognizes that students and teachers acting as partners demonstrate essential skills for citizenship – also implies a change from often accepted teaching and learning practices where students tend to be subordinate to expert faculty – this approach implies a reenvisaging of students as agents and actors with relevant, meaningful, and diverse contributions and views that can ultimately transform learning into something more meaningful for individuals and the communities in which they live.

CHAPTER 6

Potential difficulties of partnership

We recommend that you:

- Be aware of student and faculty vulnerability – be careful not to use students in disingenuous and manipulative ways – many faculty experience significant challenges in their roles, particularly when they are in part-time, pre-tenure, or non-tenure track appointments – we need a restoration of dignity for academic teachers by placing them alongside students and educational researchers rather than above or below them

- Consider in particular underrepresented students and faculty members – underrepresented students and faculty may be at particular risk for being left out of student-faculty partnership efforts if they are overlooked by those who run such programs or if they feel that, as with many structures and opportunities in higher education, these projects do not speak to their interests or needs

- Be careful and intentional regarding the language you use to describe partnership – “seeking student perspectives on questions of teaching and learning”

“inviting students to consult on approaches to pedagogical practice”

“collaborating with students to design courses”

“partnership” is too formal a word whereas “team” or “planning group” is better

- Directly address power issues – we advocate striving to find a balance of participation, power, and perspective – neither the faculty member nor the student simply asserts power or succumb to the other’s beliefs

- Start small – begin with a modest effort and allow time for the partnership to grow in depth and breadth – give yourself and your partners time and opportunity to take manageable steps

- Be wary of adopting student-faculty partnership processes and programs uncritically – the complex and nuanced nature of student-faculty partnerships in different contexts requires deliberation and adaptation, rather than assuming a one-size-fits-all – it is important that we are reflective about our own practices over time, checking to see whether we have fallen into bad habits about the levels of partnership we are facilitating, the language we are using, and which students are involved

- Keep in mind institutional contexts and larger constraints – they vary widely in their receptivity to revisions of inherited routines and their capacity to support change – participation can be used as a commodity or formula by agencies which can be marketed as part of a corporate image to assist with reputation building – in other institutions senior faculty and administrators conceptualize partnership in more meaningful ways – colleges and universities that have a strong teaching mission often provide fertile ground for student-faculty participation

- Do not assume that all students and faculty will embrace a partnership model – many students will be new to the idea of student-faculty partnerships and they may not have clear ideas to contribute to discussions and negotiations on the first day – students, like faculty, will need time to adjust to what student-faculty partnerships are and the range of partnerships that might be possible

Adobe Acrobat document [500.2 KB]

Adobe Acrobat document [6.2 MB]

CHAPTER 7

Practical strategies for developing student-faculty partnerships

Come in with an open mind about how much you can change your perspective, but do not get hung up on a perceived need for a radical change in your pedagogy: one of the most valuable things about this work for me has not necessarily been learning completely new ideas, but rather forcing me to think through, articulate, refine, and put into a stronger framework the techniques I have in place.

Wide range of outcomes from affirming techniques you already use to making minor changes or even totally revising pedagogical approaches

One end of a continuum might be anchored in full-scale collaboration across an entire course or program, while the other end rests on students being invited to make a meaningful choice about an element of a course, such as which reading or topic they would like to explore in depth.

Strategies:

- Getting started with student-faculty partnerships

- Start small – it’s practical and prudent – this is a long-term orientation rather than a quick fix – begin with an approach that seems manageable in your particular context – after a course is complete sit down with a few former students to discuss possible revisions for the next time you will teach the course

- Be patient – anticipate a few bumps – some students may not have experienced many alternatives to didactic teaching (didactic = in the manner of a teacher , particularly so as to treat someone in a patronizing way) – many students find partnership a bit uncomfortable at first – partnerships take time to develop – try to be patient, because both you and your students will need time to adapt to new partnership roles and to think about new perspectives that emerge

- Invite students to participate rather than requiring participation – partnership should be voluntary – someone needs to take the initiative – faculty typically act as gate-keepers of curriculum design – being clear and welcoming – if you are patient enough to allow the invitation to be considered and, ideally, accepted willingly, the result will be a more genuine partnership – invitations that students read as requirements undermine the goal of partnership

- Think carefully about whom to involve in the partnership – think clearly about your criteria for selecting students – high-achieving students whom they know well already – seek out students with particular subject knowledge, technology skills, or perspectives on relevant issues – interpersonal dynamics – students inclined to engage seriously, to question critically, or to think creatively – students who know nothing about the subject – underrepresented students to counter the sense of exclusion many of these students feel – partnerships thrive when well-intentioned people work together across differences

- Work together to create a shared purpose and project – first task is to give away the project – for a partnership to succeed, it needs to become shared work “our project” not mine or yours – “Let’s all participate actively and critically in this work, and together let’s monitor our group dynamics to make sure we’re as respectful, reciprocal, and responsible as we can be.” – revisit, revise, and reaffirm your goals in order for students to realize that their views and actions are being taken seriously

- Cultivate support – you only need one or two colleagues or a single person in a key role to make this work feel a lot more achievable

- Learn from mistakes – build critical, collaborative reflection into partnership process – discussion – keep journals – anonymous reflections – all participants read and respond to – interviews of participants by someone who is not a part of the group

- Sustaining and deepening student-faculty partnership practices

- Integrate partnerships into other ongoing work – integrating partnerships practices into other ongoing work can be essential to sustainability – what activities do you or your students already do that could regularly involve partnership (teaching, pedagogical planning, course feedback, programs offered by your teaching and learning center) – aim to weave partnerships into existing activities – you have the freedom to explore and experiment without being under anyone’s surveillance or judgment – partnership requires risk – there is a great deal of flexibility for creative partnerships to flourish within the structure of learning outcomes and assessments

- Give and get credit for working in partnership – think carefully about the benefits of your efforts for everyone involved in the partnership

- Include varied and diverse perspectives in partnerships – dialogues across differences of position and perspective – fresh insights – deeper engagement in teaching and learning – partnership experience should both affirm and challenge participants to think critically, take risks, and develop new ways of talking with one another about teaching and learning – with each structured support, participants can build enough trust to talk honestly across differences – one of my greatest realizations from this work is that there is a real difference between being a teacher and being a professor. Professors are experts in their field, but they are rarely given the opportunity to learn and discuss what it means to be a teacher

- Consider professional development for faculty and students involved in partnerships – to think reflectively about other aspects of partnership practices, you may want to pursue (or create) professional development opportunities for you, your faculty colleagues, and your students – professionals in your institution’s office of student affairs typically coordinate training for students on group processes, leadership, difficult dialogues, and similar topics

- Value the process – value the processes of collaborative pedagogical planning and not just the products

- Formally end a partnership when it is time – all partnerships end – work is completed, students graduate, or faculty priorities change – time to reflect and relish – use your end point as an opportunity to think together one final time about your shared and individual accomplishments and learning experiences as well as the challenges you faced

- Negotiating rules and power within partnerships

Within the parameters either implicitly or explicitly set up for student engagement within classrooms, students actually have very limited agency – in many aspects of learning, structures and processes are organized in ways that prescribe to students what they must do, when they must do it, and how they should behave – in other ways students are encouraged to take on a passive role and voice in learning processes – this passivity then constrains the student’s autonomy and the capacity to take responsibility while simultaneously reinforcing faculty power and authority – that partnership asks many students and faculty to step into unfamiliar territory that can initially lead to resistant responses

Hegemony: when a teacher within a classroom takes a stance that only allows for his or her perspective and within which students are expected simply to accept and acquire that perspective – in contrast you have a classroom within which students are guided by faculty to develop a discourse through which they name and transform knowledge, then you have a classroom that fosters the development of agents

Learning is generated through discourse, and if you wish to strive for a classroom in which students have agency, then students must have voice

Shared authority: power with mutual teacher-student authority – embracing a more democratic approach to learning and teaching premised on respect, reciprocity, and shared responsibility can lead to deeper, more engaging learning

- Before you begin, think about your own attitudes

- Designing a course or elements of a course – sharing control of assignments as a way of making students more accountable for the subject matter of the course and affording students an opportunity to learn that content more deeply, since having to craft questions or activities that assess learning is much harder than simply answering other people’s questions

- Responding to the student experience during a course – involves faculty asking for feedback partway through a course. In order to enhance the likelihood of students feeding back anonymously, often faculty leave the room for students to have faculty-less discussions

- Assessing student work

What is important is that you are clear about what is and is not in play, explaining and making transparent why some things are considered in or out of bounds.

Negotiation does not mean that you have to do everything that your students suggest or request, but neither does it mean that you can simply dismiss every point that students raise.

If you integrate some of the students’ suggestions and offer explanations of why you choose not to integrate others, students will understand that you have taken the process seriously.

- Develop ways to negotiate within the partnership

Both students and faculty may lack experience of negotiating within partnerships.

It may take time for them to develop effective methods of communicating wishes, learning to compromise, and learning to listen to others’ wishes.

Learning to compromise and to build consensus may require both faculty and students to develop new skills.

Collaboratively setting ground rules can often be a useful opening exercise to discussions about what negotiation means and how decisions will be made within partnerships.

- Be honest about where power imbalances persist

Be clear with students about what level of partnership is possible and whether faculty maintain sole responsibility for decisions over areas of the curriculum such as assessment.

Is mutual respect central to my partnership with students?

Is our partnership unfolding in a way that we are both/all putting something meaningful into it and getting something meaningful out of it?

Are we all being responsible to the other participants with whom we are working?

Respect is particularly apparent in strategies that embrace patience, that constitute invitations rather than requirements, and that see mistakes as opportunities to learn.

Reciprocity underpins strategies that support students and faculty in working together to create a shared project or approach, cultivate supportive relationships within the college community, consider ways of rewarding partnerships, and value the process.

Responsibility is particularly evident in thinking carefully and critically about whom to involve in partnerships and how to involve them, seeking to include diverse perspectives in partnerships, developing ways to negotiate partnerships, and honestly acknowledging where power imbalances remain.

CHAPTER 8

The process of establishing and nurturing partnerships typically is part of a long conversation full of questions, some possible answers, more questions, and some more possible answers.

The idea of partnership is not that all power or other differences are eliminated. Indeed, for partnership to function well, participants need to acknowledge explicitly that power exists within, and typically complicates, the relationships of those involved.

The key to student participation is offering real partnership.

Be patient, be persistent, be authentic.

There is no particular profile of a GOOD student partner; rather, any student who is willing to commit the time and attention necessary to collaborate can be a good partner because he or she brings a perspective and set of insights that we as faculty do not have.

Consider a combination of carrying forward some of what previous students co-created with you and inviting a new group to modify or expand upon what had been done. In this way, you both honor the previous effort and invite the current group to share the ongoing responsibility for developing courses or course components.

Change is at the heart of learning. What we mean by change, however, can vary widely. Some partnerships might yield a new awareness and also a reaffirmation of existing teaching. Others might open up the possibility of different practices or even entirely new approaches. Still others might prompt radical transformation, altering the foundational assumptions a faculty member has about learning, teaching, and students. One kind of change is not preferable to another in all cases. We see change on a continuum, without an idea lend point for all faculty and students. Because of this variation, we suggest faculty and students talk together about the kinds of change both partners hope and expect might result from the work, and that your work may not meet all of your expectations.

The point of partnership is not to defer to the student perspective or automatically substitute students’ recommendations for your own existing, often well-thought out, practices. The idea is to engage in dialogue that stretches and challenges your thinking so that you might act even more intentionally in your teaching, regardless of whether that means continuing what you are doing but doing it more deliberately, tweaking your current practices in small ways or explaining more clearly to students why you do what you do, or perhaps even making major revisions.

An excellent resource for re-centering conversation has been created by Student Participation in Quality Scotland (SPARQS)– an organization that supports student representation in higher education institutions across Scotland. SPARQS uses the visual metaphor of a sound engineer’s control board in a recording studio to emphasize the importance of helping students to get the volume and tone just right – not so quiet or meek that students’ views are unheard, but not too far into the “red” loud and angry zone that might prompt faculty to turn away. This tool is not meant to imply that only students have a responsibility for getting volume and tone right, as faculty still have a responsibility for facilitating dialogue in partnerships in ways that ensure all voices are heard. But this metaphor, and its related tools, could be used as a starting place for dialogue between faculty and student partners.

Faculty who have worked in partnership with students not only find ways to invite greater engagement and participation from students in their classes, they invite more of their colleagues into discussions of teaching and learning. Having a positive language to talk about teaching and learning and having experienced the gratification of talking in meaningful ways, inspires faculty to sustain and to extend such experiences.

Similar to their faculty partners, students who have worked in partnership develop the confidence and courage to respectfully approach other faculty members or employers to convey their perspectives in constructive ways – and to recognize when such efforts may not be wanted.

Partnership, after all, is one powerful way to help our students become the critical, independent thinkers and skillful global citizens that our universities aim to develop.

CHAPTER 9

Our main focus with assessment is not those familiar, institutionally mandated end-of-term student ratings. While we start with a discussion of that practice, our emphasis is on assessing student-faculty partnerships with a goal of documenting and improving them.

“assessment” – used differently in different countries and contexts – the process of stepping back from and analyzing progress in any educational endeavor – learning, teaching, research, pedagogical partnership – either in a formative way (during the process with the goal of using what is gathered to revise the approaches we are using) or in a summative way (with the goal of evaluating what has been learned, taught, or accomplished after the process is completed).

Students’ role is assessing teaching and learning in higher education

- Assessing teaching and learning within courses – if you gather student feedback at one or more points during the term and share it with the class, you can promote “two-way communication with learners” and facilitate “open discussions about course goals and the teaching-learning process” in which students feel “empowered to help design their own educational process” – research demonstrates that when faculty gather student feedback in appropriate and well-supported ways during the term, their end-of-course ratings improve

Stop – start – continue: technique that usually applies to the faculty member’s behavior – what students would like the teacher to stop doing, start doing, and continue doing in order to enhance learning – students can also be asked to offer three statements of what they individually should stop, start, and continue doing in order to enhance their own learning and that of their peers. – a partnership approach to gathering mid-semester feedback combines the in-class collaborative approach with a student-faculty partnership based outside of the class.

- Assessing teaching and learning across courses – collaborating with students to investigate educational practices across courses has a precedent in student voice activities in primary and secondary schools that focus on students as researchers. This work promotes partnerships in which students work alongside teachers to mobilize their knowledge of school and become change agents of its culture and norms. – the practice of student-faculty partnerships also has deep roots in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL)– both the student voice work in schools and partnership projects in SoTL share a commitment to inviting students into emerging communities of practice, seeing roles for them not as objects of study, but as co-inquirers, collaborators, and partners in formulating questions, generating and analyzing data, making sense of findings, and lobbying for change – such an approach requires new notions of power that in turn mean greater ability to act and thus a greater sense of responsibility

Assessing outcomes: principles of good practice

Good practice also involves attention to both formative and summative assessment. You will want to create the combination of approaches that will be most helpful to you in your context and with your goals. Different forms of investigating student-faculty partnerships are appropriate, and different ways of documenting partnership processes and outcomes are useful to different audiences.

Formative assessment

It is important that you communicate before and during the creation of student-faculty partnerships. Formative assessment is one way for you to ensure that you are engaging in just such intentional communication.

Strive to provide regular opportunities for participants and, where relevant, facilitators to step back from their work and analyze how it is unfolding. This form of dialogue gives everyone involved the chance to make mid-course corrections, to change directions when necessary, and to clarify and affirm what is working in the partnership.

Summative assessment

While formative assessment gives participants an opportunity to reflect on, revise, and learn from their work in progress, summative assessment of student-faculty partnerships provides the opportunity to take a step back to gain perspective on the arc of the work and to document its outcomes for both internal and external audiences.

CHAPTER 10

The fruits of partnership

On the one hand, partnerships can build upon familiar practices, such as gathering feedback to make changes in our practice; on the other hand, they can shift the very ground that we are standing on by asking us to rethink our foundational understandings of teaching and learning. By premising student-faculty relationships on respect, reciprocity, and shared responsibility, we can take common practices to a much deeper level. Doing this entails working within and sometimes against norms in higher education. By developing and sustaining partnerships, we can build on small-scale examples of collaborative practice among faculty and students as well as pioneer larger scale initiatives and create new visions of ways of working more suited to our emerging global society.

Next steps

Several interrelated areas

- Expanding student-faculty partnership work into new contexts – the landscape of higher education is changing – technology is enabling the creation of new pedagogies and disruptive educational formats – participatory culture

Web-based communities, like some grassroots organizations, that enact participatory culture are characterized by:

- Low barriers to entry

- Strong support for sharing one’s contributions

- Informal mentorship, from experienced to novice

- A sense of connection to each other

- A sense of ownership in what is being created

- A strong collective sense that something is at stake

- Connecting with more diverse students – each differently positioned student has unique insights to offer, and at the same time, collectively, differences can be conceptualized not only as resources but also as what we have in common, elements that can unite us – this work, while emphasizing the importance of including and accommodating unheard voices, also argues for creating a new space in which diversity and difference are seen as the very conditions for engagement in the first place, rather than being viewed as an add-on or a separate issue

- Preparing a new generation of faculty for a new kind of higher education – working closely with faculty to explore teaching and learning not only from the other side of the desk but also, as many students put it, behind the scenes, gives students a more realistic idea of what it takes to teach at the university level. It also prepares them to lead the way in creating higher education cultures and institutions that embrace the potential of student-faculty partnerships.

Toward a partnership movement!

Students are the university’s unspent resource – if there is to be a single important structural change during the coming decades it is the changing role of students who are given more room in defining and contributing to higher education.

Way #1: organizational approach – premised on the notion that bureaucracies – their rules, roles, and relationships – define the limits of social reality within which change must happen.

Formal power – strive to achieve their aims by reorganizing structures and negotiating with established authorities – change comes through curricular reform or administrative shake-ups or external disruptions

Way #2: way of the movement – activists develop power structures outside of formal organizational structures – only after building capacity and momentum among like-minded individuals did they attempt to reform social frameworks – the genius of movements is paradoxical – they abandon the logic of organizations in order to gather the power necessary to rewrite the logic of organizations

Movements typically progress through 4 stages:

- Isolated individuals decide to stop leading divided lives – they start acting in ways congruent with their own values, even though that is outside the norm

- These individuals discover each other and form groups for mutual support

- Moves from linked individuals to a more public presence and effort

- Movement gains momentum – alternative rewards emerge to sustain the movement’s vision, which may force the conventional reward system to change

Movements rarely flow neatly through these 4 stages however.

More often, progress is halting or inconsistent. Sometimes change stalls and a local movement must begin again from the start. Other times, small steps build steadily at a pace that even the most optimistic participants could not have anticipated – hope in the dark

Margaret Mead: Never doubt that a thoughtful group of committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.

Dunne and Zandstra (2011) advice for developing student-led projects:

- Start with a small number of projects that are manageable; put time into making sure they are successful and that the results are worthwhile.

- Maintain a constantly positive stance, looking for good practice rather than focusing on the less good, since this allows forward progress and the valuing and acknowledgement of staff who are doing things well.

- Ensure that students involved in any project have agreed who is going to be responsible for what, and be clear with students about expectations for working arrangements and their role.

- Have high expectations of the students but always be available in the background, and make it clear they can contact you as they need.

- Keep in contact with students throughout a project and gain ongoing feedback on progress. This keeps the momentum going but also ensures that help and support is given as required.

- On occasion, students may need support in finding strategies to work in ways that are not seen as intrusive or threatening, and therefore alienating to staff; talk through ideas for doing this.

- Be sensitive to different perspectives (from senior management, academics, professional services and support staff as well as students) and get buy-in to ensure change is taken on board.

- Make sure that positive outcomes are shared with appropriate parties and seek strategies for doing this – ongoing success may depend in part on visibility. Having a conference at the end of the year gives an absolute deadline that provides an incentive for completing projects.

Adobe Acrobat document [848.0 KB]

Contact Me

Sarah Nilsson, J.D., Ph.D., MAS

602 561 8665

You can also fill out my

Get Social with Me

Legal Disclaimer

The information on this website is for EDUCATIONAL purposes only and DOES NOT constitute legal advice.

While the author of this website is an attorney, she is not YOUR attorney, nor are you her client, until you enter into a written agreement with Nilsson Law, PLLC to provide legal services.

In no event shall Sarah Nilsson be liable for any special, indirect, or consequential damages relating to this material, for any use of this website, or for any other hyperlinked website.

Steward of

I endorse the following products

KENNON (sun shields)